I wrote this appreciation of Poor Sailor for my Comic World News column, but then I realized that mini-comics fans would probably dig a peek at this hardcover version as well....

Just when I’m getting completely fed up with all the chatter about how to save comics and what’s wrong with comics, a package arrived on my doorstep that reaffirms why I love comics so damn much. The package was a surprise, a book that I didn’t even know existed, and one that I didn’t even know was in the works.

It was a hardcover version of one of the most memorable mini-comics of the last few years - Sammy Harkham’s Poor Sailor. This little gem has been sold out at the usual outlets for more than a year, but luckily I could still point to it’s appearance in Harkham’s excellent anthology Kramer’s Ergot (volume 4 features Poor Sailor). Unfortunately, the format of Poor Sailor in KE4 isn’t as arresting as that of the mini-comic. The panels are four per page in the anthology, and increasing the panel per page count messed with the rhythm established in the mini-comic edition. With the hot off the presses Gingko Press hardcover, however, the format has returned to the original single panel per page layout.

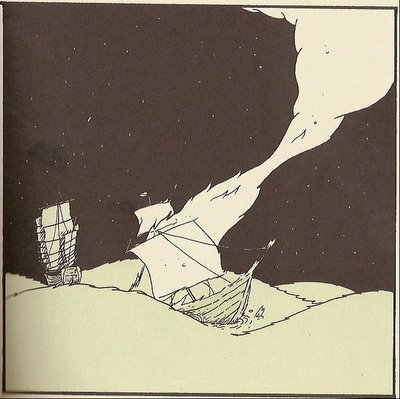

Sammy Harkham’s Poor Sailor, inspired by Guy De Maupassant’s At Sea, is a haunting tale of loss and recovery told in an unusually restrained and subtle manner. As I’ve already mentioned each page is a single panel of story. The panels are sparse, often simply pictures without words, and as you flip the pages you fall into an easy tempo with the story. The flipping of the pages actually works to pull you in; you’re the engine that propels Harkham’s tale onward. You become a part of the book, which seems like a given in comics, but it so rarely works so effortlessly. Reading Poor Sailor is one of those rare, magical experiences that makes comics just so special.

Thomas, the “sailor” in the book, enjoys a quiet life with his wife Rachel. They live in a simple thatched roof hut that’s surrounded by rolling hills. At night, they sleep holding onto each other. They gather the clothes off of the line as a couple. They walk hand in hand under the gaze of the full moon. They stare into each other’s unblinking eyes, holding hands again, as they stand naked in the water of a waist deep pond. It’s an ideal world for the couple – until a man with a mustache appears on the horizon.

The man is Thomas’s brother Jacob, a sailor who is in port for just a few days. Using stories of his exploits, Jacob fills Thomas’s head with alluring visions of the open sea and exotic ports of call. The next several pages show Thomas and Jacob walking over the rolling hills; Rachel doesn’t show up again until Harkham shows the couple at dinner one night. It’s not said in the comic, but you know what Thomas is asking as they sit at the table. Rachel is adamant in her refusals, “No Thomas. What about the house? What about me?” Thomas just stares into his plate, his knife and fork held helplessly in his hands.

After that dinner, Thomas stares a lot. He stares into the horizon when he’s chopping wood, he stares into the darkness as he tries to sleep. And then one night, sitting up in bed he says Rachel’s name softly. He repeats it once and then touches her sleeping figure with his hand, whispering, “I’ll come back soon.”

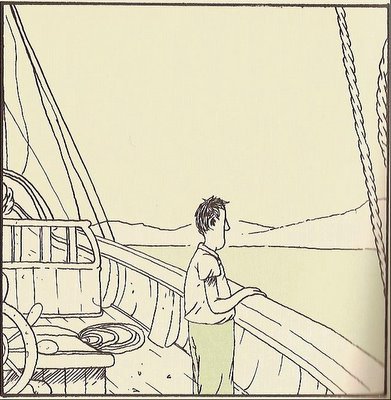

At this point you’re only a third of the way through the book, there’s much more to come, but it’s a dividing line in the tale. Harkham has said so much with so little words up to this point. He uses the visual language of comics to show a happy couple, and then just like that Thomas is gone. We won’t see Rachel again. Well, we will see her in a way much later in the book, but now the book becomes Thomas’s story alone. Thomas does go to see with his brother. But his decision is costly.

His experiences at sea are lively and varied. It’s a new life for Thomas, but one day, during a rare, quiet moment on the side of a hill, he pictures his wife Rachel. There aren’t any thought balloons to telegraph what he’s thinking at that moment, but it’s obvious. He’s wondering if his decision to leave his simple life was worth it, especially in light of what his decision costs him at sea. (I’m not telling you what happens, but he does eventually return home).

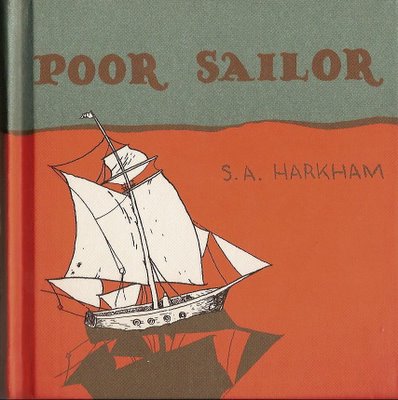

In this format, Poor Sailor reminds me of a children’s book designed for grownups. It’s got that colorful children’s book cover. Across the top is a pale green sky with the title floating in orange; underneath the title, you find a white ship with sails full of wind slicing through an orange sea. Inside, the bright orange from the cover splashes across the endpapers. As you flip to the story, the pages turn green, giving you a preview of the only color used to offset the black and white of the art. The dimensions of this 128-page book are perfectly square at 5 ½” x 5 ½”.

This Gingko Press edition was published in December of 2005 and it retails for $14.95. I also suggest a peek at Sammy Harkham’s website. Good stuff.

No comments:

Post a Comment